Obsessive Compulsive Disorder—Myths and Misconceptions

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a complex and often debilitating mental health condition that affects millions of people around the world.

Posted on 25 Jun 2024

Written by

Dr Jared Ng, Connections MindHealth

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a complex and often debilitating mental health condition that affects millions of people around the world. The 2016 Singapore Mental Health Study (SMHS) highlighted OCD as one of the top three most common mental disorders in the country [1]. The findings revealed that approximately one in every 28 adults in Singapore has been impacted by OCD, sparking discussions that Singapore might be the “OCD capital” of the world.

Characterised by persistent, unwanted thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviours or mental acts (compulsions), OCD can significantly interfere with a person’s daily activities and quality of life. These obsessions and compulsions are not simply excessive worries about real-life problems or personal quirks; they are intense, consuming, and distressingly intrusive.

Despite its prevalence and severity, numerous myths and misconceptions about OCD persist, which can lead to stigma, misdiagnosis, and inadequate treatment. The 2016 SMHS suggested that the duration of untreated OCD was slightly more than 10 years, underscoring the critical need for awareness and timely intervention. Misconstruing OCD and its impacts trivialises the condition and obscures its true nature [2], preventing those affected from seeking help or receiving the empathy and support they desperately need.

This article aims to debunk some of the biggest myths about OCD and provide a clearer picture of what the disorder is. By spreading accurate information and fostering a better understanding of OCD, we hope to create a more compassionate environment that encourages those affected to seek treatment and supports them on their road to recovery.

Content

- Understanding OCD; The relationship between Obsession and Compulsion

- Dispelling Popular Myths: The Realities of OCD

- Myth 1: OCD is just about being overly tidy and organised

- Myth 2: People with OCD just need to relax and stop worrying

- Myth 3: OCD is not a serious disorder

- Treatment and Management of OCD

- Importance of Seeking Professional Help

- Moving Beyond Misconceptions; Resources for Further Reading or Assistance:

Understanding OCD; The relationship between Obsession and Compulsion

One of the core aspects of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) that is often misunderstood is the distinction and relationship between obsessions and compulsions. These two components are the hallmark features of OCD, but they manifest differently and serve different psychological purposes in the disorder.

Obsessions:

Obsessions are involuntary, persistent thoughts, images, or impulses that intrude into a person’s mind and cause significant anxiety or distress. These are not simply excessive worries about real-life problems but are often irrational or exaggerated fears. People with OCD typically recognise that their obsessions are created in their minds but are unable to control or dismiss them.

Examples of less visible obsessions include:

- Fear of accidentally harming oneself or others, even in “absurd” or unlikely scenarios.

- Intrusive sexual thoughts or images that are distressing.

- Obsessions with symmetry or exactness, where a slight imperfection can trigger intense discomfort.

- Fears of shouting obscenities or acting inappropriately in public which lead to social withdrawal.

Compulsions:

Compulsions are repetitive behaviours or mental acts that a person feels compelled to perform in response to an obsession or according to rigid rules. The primary purpose of these compulsions is to prevent or reduce the distress caused by the obsessions or to prevent a feared event or situation; however, these behaviours are either not connected logically to the feared event or are excessive.

Examples of less visible compulsions include:

- Mental rituals, such as repeating certain words or phrases in one’s mind to ward off harm or bad luck.

- Counting objects or performing tasks in certain numbers to “neutralise” the anxiety associated with an obsession.

- Rearranging or organising items until they feel “just right” to alleviate the distress of imperfection.

- Silently praying or performing rituals that cannot be observed by others, which can often go unnoticed.

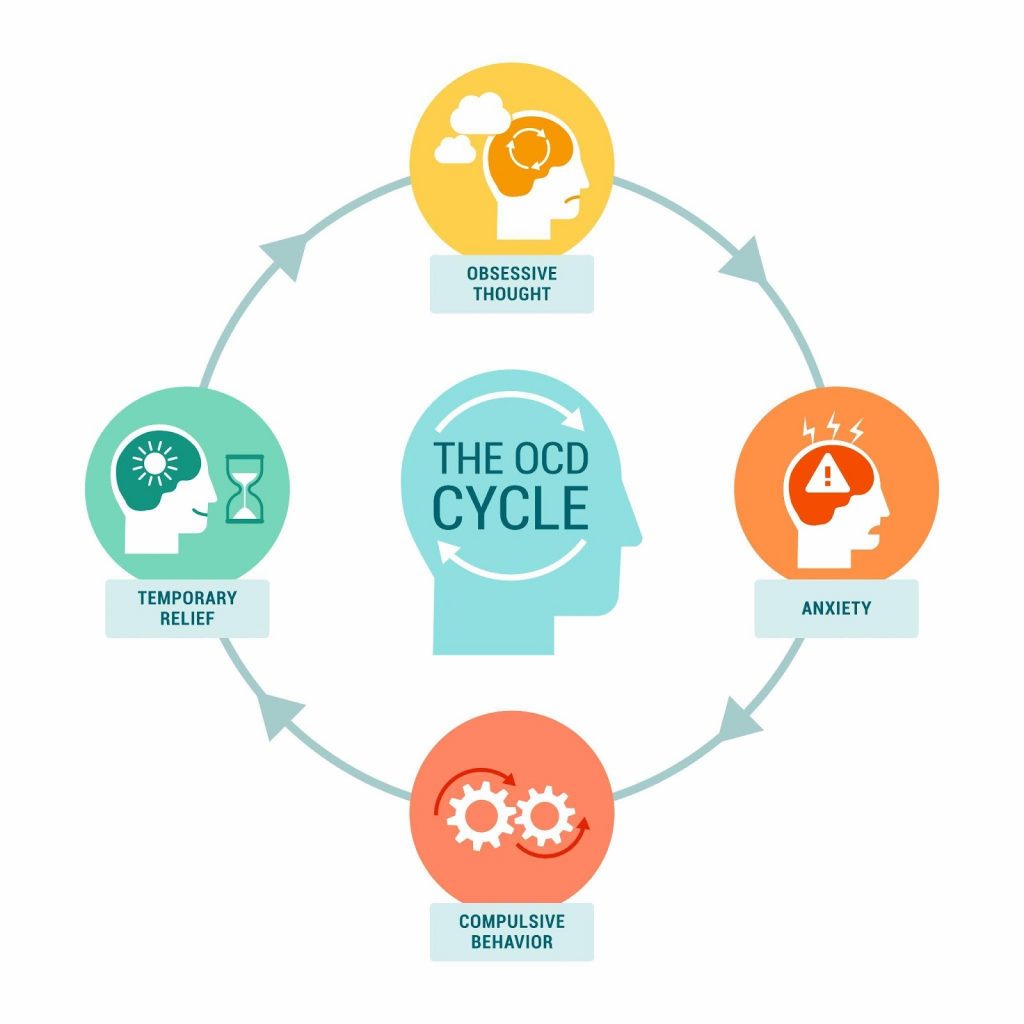

The relationship between obsessions and compulsions in OCD is one of a problematic cycle. Obsessions fuel anxiety, which compels the individual to engage in compulsive behaviours. These compulsions temporarily reduce the anxiety but reinforce the obsession, which makes it even stronger. This creates a vicious cycle that can escalate and become more debilitating over time.

Dispelling Popular Myths: The Realities of OCD

Myth 1: OCD is just about being overly tidy and organised

One of the most common misconceptions about Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is that it solely manifests as a preoccupation with cleanliness and a need for order. This stereotype is often perpetuated by media portrayals and casual references that equate being meticulous or neat with having OCD. However, this simplistic view fails to capture the complexity and distress that characterise the disorder.

Comparison with Normal Tidiness:

While many people prefer a clean and organised environment, those with OCD experience severe anxiety if things are not “just right.” For example, a person without OCD might feel satisfied after tidying up their desk, but someone with OCD might spend hours arranging and rearranging items to achieve a sense of relief from their distressing thoughts.

OCD is a clinical condition marked by severe and intrusive obsessions—unwanted thoughts, images, or urges that repeatedly enter the mind and cause significant anxiety [3]. These obsessions are coupled with compulsions, which are behaviours an individual feels compelled to perform in an attempt to reduce stress or prevent some dreaded event or situation, regardless of whether these outcomes are realistic.

The manifestations of OCD can be extraordinarily diverse. Beyond the well-known compulsions related to cleanliness, such as hand-washing or sanitising, OCD can involve:

[wpcode id=”1826″]

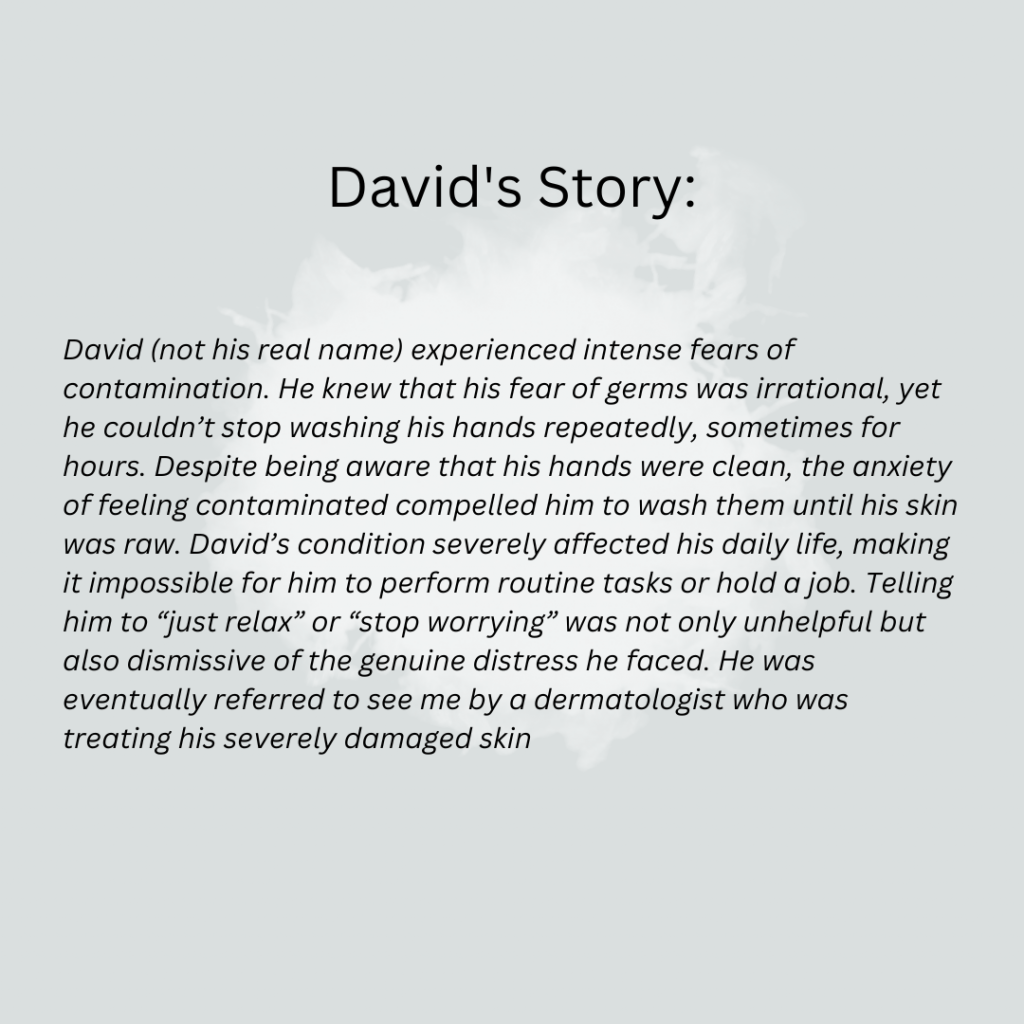

Myth 2: People with OCD just need to relax and stop worrying

A common but harmful misconception about Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is the notion that individuals can simply choose to ‘relax’ or stop worrying to overcome their symptoms. This belief undermines the serious nature of OCD and suggests that it is within the individual’s control to stop their obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours. In reality, OCD is a deeply ingrained disorder with complex biological and psychological roots, and it is not about lacking willpower or personal strength.

Biology of OCD Explained:

OCD has a significant biological basis. Research has shown that genetic factors play a crucial role in the development of the disorder, with individuals having a higher risk of developing OCD if a close family member also has the condition [8]. Neuroimaging studies have revealed that people with OCD often have differences in certain areas of the brain, including the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and basal ganglia [9]. These brain regions are involved in decision-making, learning from mistakes, and controlling repetitive behaviours. Abnormalities in these areas can contribute to excessive doubts, compulsive checking, and the intense need to perform rituals that are characteristic of OCD.

- Serotonin and Brain Function:

The role of neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin, has also been highlighted in the pathology of OCD [10]. Serotonin is crucial for mood regulation and decision-making processes. Imbalances or disruptions in serotonin levels can exacerbate the symptoms of OCD, which can result in increased anxiety and the compulsion to perform certain rituals [11]. This is why medications that target serotonin levels, such as SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), are often effective in managing OCD symptoms.

- Psychological Factors:

From a psychological perspective, OCD is believed to be influenced by behavioural, cognitive, and environmental factors. For example, behavioural theory suggests that compulsions are developed to reduce the anxiety caused by obsessions temporarily [12]. Cognitively, people with OCD may have maladaptive beliefs about responsibility and harm, overestimating the danger in certain situations and their role in preventing it. This can lead to excessive checking, hoarding, or other compulsive behaviours.

- Why It’s Not About Willpower:

Telling someone with OCD to stop worrying or to relax is akin to telling someone with asthma to breathe normally during an asthma attack—neither helpful nor feasible. OCD is not a disorder that can be controlled or willed away by the individual. It requires professional treatment, including therapy and sometimes medication, to manage effectively.

Understanding these biological and psychological underpinnings of OCD helps highlight why reducing it to an issue of willpower is not only incorrect but also detrimental. It diminishes the real struggles experienced by those with the disorder and can prevent individuals from seeking the appropriate, evidence-based treatments that they need.

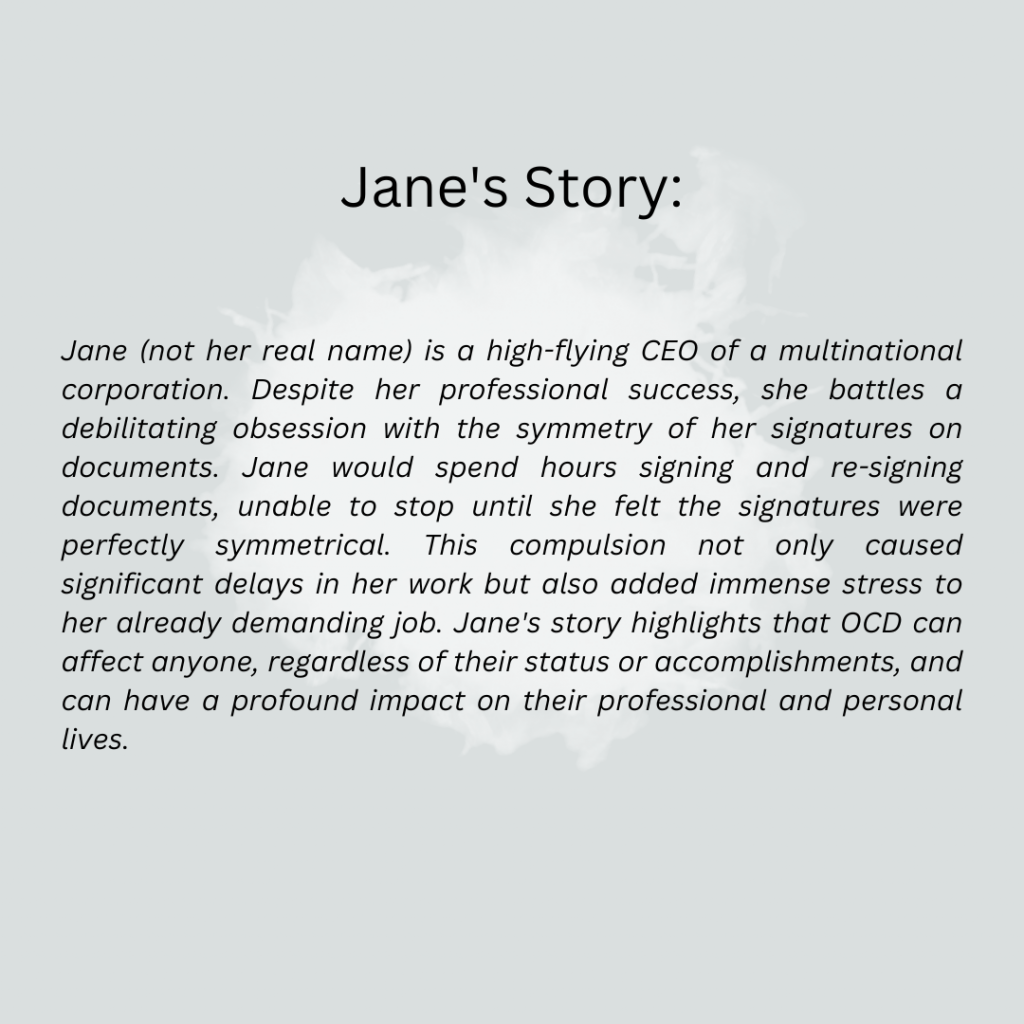

Myth 3: OCD is not a serious disorder

Contrary to the dismissive views that label Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) as a minor annoyance or a mere personality quirk, OCD is a serious psychiatric condition recognised for its serious impact on daily functioning and overall quality of life. The idea that OCD is not a significant health issue is not only inaccurate but also diminishes the real and sometimes severe challenges faced by those who live with the disorder.

According to the World Bank and the World Health Organization, OCD is the tenth leading cause of disability globally, and for women aged 15 to 44 years, it ranks fifth. [13]. Studies have shown that individuals with OCD can experience a reduction in quality of life that is comparable to or even greater than those suffering from chronic physical conditions like diabetes [14]. The economic impact is also significant, with many individuals facing challenges in maintaining consistent employment and managing healthcare expenses related to their condition.

The data and real-life impacts illustrate that OCD is undoubtedly a serious disorder, deserving of the same attention and medical care as any other significant health issue.

Impact of OCD on Daily Life:

OCD can severely disrupt daily activities by making routine tasks extraordinarily difficult and time-consuming. For many individuals, the intense need to perform compulsive rituals—such as repeated hand washing, checking, or arranging items in a specific order—can take up several hours of their day, which severely disrupts their personal, professional, and social lives. The distressing nature of obsessive thoughts can also lead to heightened anxiety, pervasive feelings of disgust, or even a paralysing fear of harming others inadvertently. These experiences can restrict individuals’ ability to function in work settings, participate in social activities, and maintain relationships, which often leads to isolation and loneliness.

Mental Health Consequences:

The constant battle with obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours can lead to significant emotional distress. Many individuals with OCD experience co-occurring mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety disorders. The relentless nature of OCD can contribute to feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, which are key risk factors for depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Furthermore, the stigma associated with mental health, particularly around a misunderstood condition like OCD, can exacerbate feelings of shame and inadequacy, hindering individuals from seeking help and support.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is not only a complex disorder in its own right, but it is also frequently accompanied by other psychological conditions [15]. This coexistence of multiple disorders, known as comorbidity, can complicate diagnosis and treatment, and affect the overall prognosis of those affected. Understanding the relationship between OCD and its comorbid conditions is crucial for developing comprehensive treatment plans that address all aspects of a patient’s mental health.

Common Comorbid Conditions with OCD:

- Anxiety Disorders: OCD is often found alongside other anxiety disorders, such as Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) [16], Panic Disorder [17], and Social Anxiety Disorder [18]. The overlap is understandable, given that both OCD and other anxiety disorders involve chronic worry and fear. However, OCD is distinct in that the anxiety typically stems from intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and is temporarily alleviated by specific actions (compulsions).

- Depression: Depression is one of the most common comorbid conditions with OCD [19]. The relentless nature of OCD symptoms often leads to feelings of despair and hopelessness, which can evolve into clinical depression. The presence of depression in OCD patients can make symptoms worse and recovery more challenging, as it can sap motivation and increase feelings of worthlessness.

- Eating Disorders: Eating disorders [20], particularly those involving ritualistic behaviour around food and body image, such as Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa, can also co-occur with OCD. The obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours seen in eating disorders can mirror the pattern of symptoms experienced in OCD, reflecting a shared foundation of anxiety and control issues.

- Tic Disorders: Particularly in pediatric populations, there is a significant overlap between OCD and tic disorders, including Tourette Syndrome [21]. Both conditions involve repetitive behaviours, although the compulsions in OCD are typically linked to obsessional thoughts, whereas tics are often involuntary and not connected to obsessions.

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Although seemingly counterintuitive due to ADHD’s association with impulsivity (opposite of OCD’s compulsivity), there is a noteworthy rate of comorbidity [22]. The shared features may include high levels of inattention, poor impulse control, and executive functioning problems.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): There is a considerable overlap between OCD and ASD. Individuals with ASD may engage in repetitive behaviours and routines similar to OCD compulsions, but the motivations behind these behaviours differ. Understanding the distinctions and overlaps is crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

- Autoimmune Conditions: Paediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS) is a condition where streptococcal infections lead to the sudden onset or worsening of OCD symptoms in children. This condition highlights the complex interplay between infections and psychiatric symptoms, necessitating a multidisciplinary approach to treatment.

Treatment and Management of OCD

The presence of comorbid conditions in individuals with OCD requires a more comprehensive treatment approach. For instance, a treatment strategy that only addresses OCD may not be effective if the patient is also experiencing major depressive disorder. In such cases, a combination of medications, along with therapy tailored to address both OCD and depression, may be necessary.

Moreover, the treatment of one condition can sometimes improve the symptoms of the other. For example, the techniques used in CBT for managing anxiety can also be beneficial in controlling OCD symptoms. However, healthcare providers must monitor all conditions closely and adjust treatment plans as necessary to address the full scope of a patient’s mental health needs.

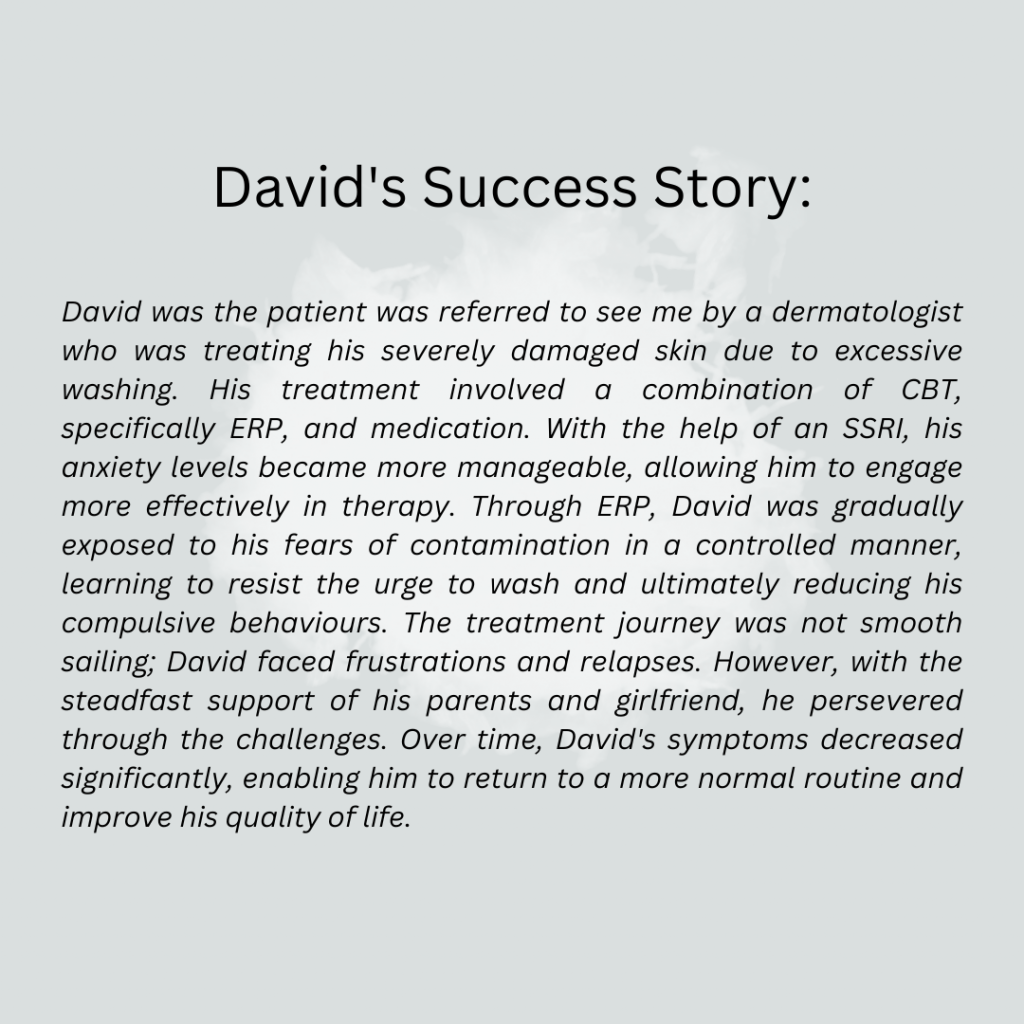

Effective treatment and management of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) are critical for improving the quality of life for those affected by the disorder. Modern treatment methods, professional help, and support from loved ones form the cornerstone of successful management strategies for OCD. Understanding these elements can empower individuals and their families to seek the right kind of help and support needed.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT is one of the most effective treatment options for OCD, particularly a specialised form known as Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) [23]. ERP involves exposing the person to the thoughts, images, objects, and situations that make them anxious or trigger their OCD symptoms. The key is to encourage the individual not to engage in the compulsive behaviour typically performed in response to anxiety. Over time, ERP can help reduce the compulsive behaviours associated with the triggers.

- Medication: Medications, especially those that increase the brain’s serotonin levels, are often prescribed in conjunction with therapy. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly used medications for treating OCD, helping to manage symptoms by balancing neurotransmitters [24]. In some cases, other types of psychiatric medications may be recommended depending on the individual’s symptoms and response to SSRIs. These include:

○ Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs): Clomipramine is a TCA that has been found to be effective in treating OCD. It works by affecting serotonin levels in the brain, similar to SSRIs, but can also influence other neurotransmitters. However, TCAs can have more pronounced side effects, such as dry mouth, constipation, and dizziness, which need to be carefully managed.

○ Antipsychotics: In some cases, antipsychotic medications such as risperidone or aripiprazole may be prescribed as adjunctive therapy, particularly if the patient does not respond adequately to SSRIs alone. These medications can help reduce intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviours but come with potential side effects like weight gain, sedation, and metabolic changes.

○ Benzodiazepines: While not typically first-line treatments for OCD, benzodiazepines like clonazepam can be used short-term to help manage severe anxiety and agitation associated with the disorder. These medications are usually prescribed with caution due to their potential for dependence and tolerance.

○ Other Antidepressants: Some other antidepressants, such as Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs), may also be effective for treating OCD symptoms in patients who do not respond to SSRIs. These medications work by affecting multiple neurotransmitters, which can be beneficial but also require careful monitoring for side effects.

Psychiatrists must balance the benefits of these medications against their possible side effects to achieve the best possible outcome for the patient. This involves careful monitoring and adjusting dosages or changing medications as needed to minimize side effects while effectively managing symptoms.

- Combination Therapy: Often, a combination of CBT and medication provides the best results. This approach addresses both the behavioural and biochemical aspects of the disorder, providing a comprehensive management strategy.

Importance of Seeking Professional Help

Managing OCD typically requires more than just willpower or self-help strategies—it needs professional intervention. Mental health professionals can provide a diagnosis, recommend appropriate treatment modalities, and adjust therapies as needed based on how the patient responds over time. Professional guidance is crucial because it ensures that treatment is tailored to the individual’s specific symptoms and severity, which can significantly enhance the effectiveness of the treatment.

Encouraging Support from Family and Friends

Support from family and friends is extremely valuable in the treatment of OCD. A supportive social network can help reduce the stigma and isolation often associated with this disorder. Family members and friends can also play a proactive role by encouraging adherence to treatment regimens, providing transportation to therapy sessions, or simply being there to listen in a non-judgmental manner.

- Education: It’s helpful for family and friends to educate themselves about OCD to better understand the challenges and behaviours associated with the disorder. This knowledge can foster patience and empathy, key components of support.

- Participating in Therapy: Sometimes, therapists may involve family members in sessions to improve understanding and communication around the behaviours and needs associated with OCD.

- Advocacy: Loved ones can also serve as advocates for individuals with OCD, helping them navigate healthcare systems and advocating for necessary accommodations at school or work.

In conclusion, the treatment and management of OCD involve a multifaceted approach that includes advanced therapeutic techniques, appropriate medication, and a strong support system. With the right combination of these elements, individuals with OCD can lead fulfilling lives despite the challenges posed by the disorder.

Moving Beyond Misconceptions

In this article, we have tackled some of the most persistent myths and misconceptions surrounding Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). These myths not only skew public perception but also contribute to the stigma and misunderstandings that can significantly impact those living with OCD. By debunking these myths, we aim to foster a more accurate and compassionate understanding of the disorder, highlighting its complexity and the real challenges faced by those affected.

Our society stands to benefit greatly from a deeper understanding and empathy towards mental health issues, particularly OCD. Empathy begins with education and awareness, which can break down the barriers of ignorance and fear that often surround mental health disorders. We encourage everyone to advocate for and promote mental health education in their communities, which can transform public attitudes and make a real difference in the lives of those affected.

- Educate Yourself and Others: Continue learning about OCD beyond this article. Education is a powerful tool for changing perceptions and promoting an environment of support and understanding.

- Support Mental Health Initiatives: Includes participating in community awareness events, supporting mental health non-profits, or advocating for policies that improve mental health care, your involvement can contribute to a larger change.

- Show Compassion: If you know someone struggling with OCD, offer your understanding and support. Sometimes, simply being there to listen without judgment can make a significant difference.

- Seek Professional Help if Needed: If you or someone you know is battling OCD, encourage seeking help from mental health professionals. Early intervention can lead to better outcomes.

Resources for Further Reading or Assistance:

- International OCD Foundation

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Books like The Man Who Couldn’t Stop by David Adam and Brain Lock by Jeffrey M. Schwartz

By addressing these myths and supporting those affected by OCD, we can create a more inclusive and supportive community. Let’s commit to being part of the solution, promoting understanding, and providing educated support to transform how we deal with OCD in society.

References

- Subramaniam, M., Abdin, E., Vaingankar, J. A., Shafie, S., Chua, B. Y., Sambasivam, R., Zhang, Y. J., Shahwan, S., Chang, S., Chua, H. C., Verma, S., James, L., Kwok, K. W., Heng, D., & Chong, S. A. (2019). Tracking the mental health of a nation: Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders in the second Singapore mental health study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, e29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000179

- Kaur, R., Garg, R., & Raj, R. (2023). Quality of life among patients with obsessive compulsive disorder: Impact of stigma, severity of illness, insight, and beliefs. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 32(1), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.4103/ipj.ipj_22_22

- Stein, D. J., Costa, D. L. C., Lochner, C., Miguel, E. C., Reddy, Y. C. J., Shavitt, R. G., van den Heuvel, O. A., & Simpson, H. B. (2019). Obsessive–compulsive disorder. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 5(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0102-3

- Hoarding ocd: Symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and more. (2023, December 21). Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/ocd/your-guide-to-hoarding-ocd-and-its-treatment

- Compulsion to touch things in ocd cases – beyond ocd. (n.d.). Retrieved May 27, 2024, from https://beyondocd.org/expert-perspectives/articles/a-touching-story

- Symmetry ocd: Compulsively orderly. (2024, January 22). https://www.simplypsychology.org/orderliness-and-symmetry-ocd.html

- LPC, S. Q. (2023, August 16). OCD themes that can be hard to talk about. NOCD. https://www.treatmyocd.com/blog/ocd-themes-that-can-be-hard-to-talk-about

- Strom, N. I., Soda, T., Mathews, C. A., & Davis, L. K. (2021). A dimensional perspective on the genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01519-z

- Parmar, A., & Sarkar, S. (2016). Neuroimaging studies in obsessive compulsive disorder: A narrative review. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(5), 386–394. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.191395

- Baumgarten, H. G., & Grozdanovic, Z. (1998). Role of serotonin in obsessive-compulsive disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. Supplement, 35, 13–20.

- The links between ocd and serotonin deficiency. (n.d.). Retrieved May 27, 2024, from https://www.calmclinic.com/ocd/serotonin-deficiency

- Foa, E. B. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(2), 199–207. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181959/

- World health organisation and ocd | ocd-uk. (n.d.). Retrieved May 27, 2024, from https://www.ocduk.org/ocd/world-health-organisation/

- Żerdziński, M., Burdzik, M., Żmuda, R., Witkowska-Berek, A., Dȩbski, P., Flajszok-Macierzyńska, N., Piegza, M., John-Ziaja, H., & Gorczyca, P. (2022). Sense of happiness and other aspects of quality of life in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1077337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1077337

- Ocd related disorders | baylor medicine. (n.d.). Retrieved May 23, 2024, from https://www.bcm.edu/healthcare/specialties/psychiatry-and-behavioral-sciences/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-program/related-disorders

- Sharma, P., Rosário, M. C., Ferrão, Y. A., Albertella, L., Miguel, E. C., & Fontenelle, L. F. (2021). The impact of generalized anxiety disorder in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Psychiatry Research, 300, 113898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113898

- Comorbidity and ocd. (n.d.). Made of Millions Foundation. Retrieved May 23, 2024, from https://www.madeofmillions.com/ocd/comorbidity-and-ocd

- Endrass, T., Riesel, A., Kathmann, N., & Buhlmann, U. (2014). Performance monitoring in obsessive–compulsive disorder and social anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(4), 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000012

- Tibi, L., van Oppen, P., van Balkom, A. J. L. M., Eikelenboom, M., Rickelt, J., Schruers, K. R. J., & Anholt, G. E. (2017). The long-term association of OCD and depression and its moderators: A four-year follow up study in a large clinical sample. European Psychiatry, 44, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.03.009

- The relationship between eating disorders and ocd part of the spectrum. (n.d.). International OCD Foundation. Retrieved May 23, 2024, from https://iocdf.org/expert-opinions/expert-opinion-eating-disorders-and-ocd/

- The relationship between ocd and tourette’s. (n.d.). NOCD. Retrieved May 23, 2024, from https://www.treatmyocd.com/what-is-ocd/info/related-symptoms-conditions/ocd-and-tourettes

- Adhd and ocd: They can occur together. (2021, March 24). Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/adhd-and-ocd

- Foa, E. B. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(2), 199–207. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181959/

- Medications for ocd » department of psychiatry » college of medicine » university of florida. (n.d.). Retrieved May 23, 2024, from https://psychiatry.ufl.edu/patient-care-services/ocd-program/medications-for-ocd/